5

Operation Colosseum

October-November 1986

“In comradeship is danger countered best.”

ON 25 OCTOBER 1986 the whole of 5 Recce converged on Oshivelo, a training area adjacent to the northern tip of the Etosha National Park. It was just across the so-called red line, dividing the farmlands to the south from the operational area to the north. The unit had come together to rehearse for Operation Colosseum – a deep penetration into Angola for a base attack on the headquarters of SWAPO’s Eastern Front. A two-man recce team – Jos? da Costa and I – would be inserted a week before the attack to locate the base and call in the attack force. This was to be our first Small Team deployment together, and both of us were a bit apprehensive, as each of us was unsure what to expect of the other.

Operation Colosseum

Jos?’s huge frame had earned him the nickname “Mr T”, after the character of BA Baracus in the popular 1980s television action series The A-Team. Depending on the big man’s mood, we would call him “Da Costa” or “Mr T”, or simply by his first name. For Operation Colosseum Mr T became my team buddy, as Vic had to catch up on promotional courses, which every operator still had to complete for promotion, and was subsequently moved to another team.

Da Costa was born in Lobito, then a lively coastal town in the Benguela province of Angola, to a white Portuguese father and a mother from one of the local tribes. Before the Angolan civil war the town had been known for its carnival – not unlike that of Rio de Janeiro – which, together with the town’s location and picturesque setting, attracted many tourists. But his blissful childhood was cut short by the civil war; Da Costa was only eighteen when the war split up his family and forced him and his sister to leave the country.

Over the years Da Costa has shared snippets of his life story and how he came to join Special Forces. I was amazed by what he had experienced by the time he was in his early twenties. It was difficult for me to imagine losing your home and your parents and having to flee for your life at such a young age. What happened to him and his family happened to thousands of other Angolan refugees. Their stories have not received as much attention from the South African media as those of former SADF soldiers, yet their experiences are just as much a part of the Border War story.

In early 1976 Da Costa arrived at Buffalo Base in the Western Caprivi with a group of ex-FNLA soldiers, who would later become the formidable fighting force known as 32 Battalion. Their familes were brought from Rundu and established in the kimbo (village) at Buffalo along the banks of the Kavango River. Da Costa’s first opportunity to do specialised work came with the formation of the reconnaissance wing of 32 Battalion. He joined up, and by the end of 1977 had moved to Omauni, the recce wing’s operational base.

By 1981 he had made up his mind to join Special Forces. Since he had experience in small team work at 32 Battalion Recce Group, he wanted to apply his skills in a specialised environment. He was also under some pressure from his colleagues, because some of the 32 Battalion soldiers were already at 5 Recce, so he and three friends started to prepare. The four of them were transferred from 32 Battalion to Phalaborwa in February 1982. In April they did Special Forces selection with a group of 30 soldiers. Da Costa was one of only six who passed, and was soon transferred to 53 Commando.

At the end of 1984, when the Small Teams commando was established at 5 Recce under the command of then Captain Andr? Diedericks, Da Costa wasted no time in applying, as he believed that, in his own words, he “was destined for greater things”.

Prior to the deployment, Da Costa and I had worked out a programme for the two weeks of rehearsals: PT every morning, and then movement techniques, including patrolling, approach methods, anti-tracking and establishing hides. The PT sessions were a combination of buddy exercises and long-distance running with boots, webbing and weapons. To carry the big man was no mean feat, as he weighed at least 20 kg more than me, but I figured I’d rather get used to it for the day I needed to carry him out of Angola. The buddy-PT with combat gear also ensured that our kit was totally prepared, that there were no loose ends, and that every single item was secured with a string. It also meant that our boots would be worked in and ready for the long trek.

Over the heat of the day we’d prepare equipment – packing rucksacks, testing radios and fine-tuning our personal webbing. The afternoon would be spent planning, preparing maps and working out SOPs for the team, which we jotted down and memorised. Escape and evasion (E&E) plans were discussed and rehearsed in the finest detail.

After dinner we did night-work sessions, going through the same drills as during the morning’s programme. We’d practise the same patrol techniques, but simulate various scenarios in the dark, applying immediate action drills to every contingency. Slowly but surely, Da Costa and I started to blend as a team. We complemented each other in every respect. We would often find ourselves doing the same thing, or following the same course of action, without even having consulted one another.

One morning after our PT session, the ever-pragmatic Da Costa raised the matter of our rucksacks again. If we took the bulky Small Team packs along on the mission, we would not have the immediate advantage of deception when spotted by the enemy. The lightweight “SWAPO” pack, on the other hand, would not be big enough for radios, food and water for seven days, as well as all the optical equipment required for a reconnaissance mission.

Da Costa suggested that we take the big packs and make sure we didn’t move in daytime. The packs could also be cached close to the target when we started the final stalk. In the end we decided to take the Small Team pack, which I was grateful for, as the SWAPO pack didn’t have a frame and could be quite uncomfortable.

When it came to our food and water, we knew that everything would have to be carried, since there was no possibility of a resupply. There would be no cooking, so the gas stoves and cylinders could be discarded. Also no tins – because of their weight. That left us with “zap”[15] meat, energy bars and peanuts. Vitamin-enriched energy drinks would round off our diet; water would make up easily 70 to 80 per cent of the total weight. Da Costa’s pack weighed in at a relatively modest 80 kg when we were finally ready to deploy.

For a patrol formation during the final approach, I would take the front, with Da Costa carrying the HF radio as usual to my right and slightly back, 20 to 30 metres, depending on the undergrowth and the moon phase. Incidentally, there would be a half-moon during our deployment; this was ideal for an area reconnaissance, as the team would have moonlight for the first half of the night, and no moon during the early morning hours – just what we wanted for a penetration.

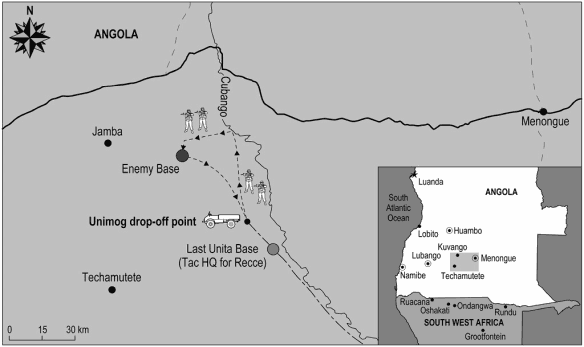

We had to make a final decision on the method of insertion. The combat force would be stationed at a UNITA base approximately 60 km from the target area. From there the reconnaissance team had to infiltrate to an area from where the final recce could be launched. It was decided that a team with three Unimogs would drop us off and return to the main force until it was time for our pick-up.

Contrary to our regular Small Teams procedures, we did not have a dedicated Tac HQ commander and signaller. The team would travel in the HQ grouping under Colonel James Hills, the OC 5 Recce. When deployed, we would talk back to the unit’s signal section at regimental HQ. This was not ideal, as it was standard procedure to have a dedicated comms system – radios, signallers, allocated frequencies and a well-rehearsed no-comms procedure – for the recce team. One certainly did not want to compete for air time when the bullets were inbound.

But Da Costa spent many hours with the HQ signallers, testing frequencies at various distances and talking them through our no-comms procedures. At the time his Afrikaans was limited to “Manne, moenie kak aanjaag nie [Guys, don’t bugger up]”, flavoured with exotic Portuguese swearwords that fortunately only he could understand. In the end he was satisfied, and the national service signalmen developed a grudging respect for the bulky Portuguese.

A day before the deployment, all the groupings were mustered for an initial Int and Ops briefing. The final briefing for the attack would be given at the forward base – after the reconnaissance. A massive sand model had been built under a double tent canopy. Major Dave Drew, the intelligence officer for the deployment, presented the general intelligence picture. Then he designated Captain Robbie Blake, at the time the intelligence officer for 51 Commando at Ondangwa, who had done a detailed target study of the Eastern Front HQ, to present the target briefing. The whole of 5 Recce, reinforced by a company from 101 Battalion and elements from 2 Recce, the Reserve Force element of Special Forces, gathered around the model.

The grouping leading the main attack consisted of Major Duncan Rykaart’s 52 Commando – supported by the company from 101 Battalion as well as elements from 2 Recce. Major Niek du Toit and 53 Commando would be deployed as stoppers to the north of the base, while Major Buks Buys would lead 51 Commando to an escape route west of the target. A mortar platoon would deliver indirect fire support. Da Costa and I, the two Small Team operators who would do the reconnaissance, filled the last positions around the sand model.

The Eastern Front HQ was a typical guerrilla base, with an estimated strength of between 270 and 350, depending on the movement of its detachments. The defence of the camp was based on two 82-mm mortars, three 60-mm mortars, three DShK 12.7-mm anti-air machine guns that could be deployed in the ground role, and a number of SA-7 shoulder-launched missiles. Early-warning posts were deployed four kilometres to the east and south of the base.

It had been gleaned from radio intercepts, direction-finding and SWAPO prisoners of war that the base was situated next to a southward-flowing river, with a vehicle track passing east–west through the base. However, the recce team would have to pinpoint the position, determine a location for the forming-up point, decide on the direction of attack, and allocate positions for the mortar platoon as well as the cut-off groups. A tall order, I thought, considering we had only six days for infiltration, reconnaissance and exfiltration.

FAPLA’s 35 Brigade was positioned at Techamutete, about 60 km northwest of the target, while tactical groups were stationed at Cassinga and Cuvelai to the west and southwest. A Cuban regiment was based at Jamba to the north (not the Jamba that served as Jonas Savimbi’s headquarters). Fighter aircraft were operating from Menongue, a mere 80 km northeast of our target.

Colonel Hills presented the Ops briefing himself. The columns of vehicles would depart from Oshivelo in the early morning hours of 3 November. By first light the convoys would be south of the border west of the Cubango River, in order to cross that night. The logistics echelon, under RSM Koos Moorcroft, would follow the next night. The whole force would regroup north of the border and head along an established UNITA route to the forward base approximately 60 km east of the target area. From there the recce team would be deployed, while the attack force would remain in position until they returned.

When I caught Da Costa’s eye, his faced was pulled into a grimace. I knew what he was thinking: it went against all principles to do a reconnaissance against time, especially where the success of the attack depended entirely on what the recce team reported. Moreover, we both understood that if the team was compromised it would mean certain failure, as the attack would have to be called off, or – worse – that the enemy could be ready and waiting for the attack force.

When I told Colonel Hills after the briefing that there was not enough time for a proper reconnaissance, and that we should have deployed earlier, he just said, “Vasbyt, Kosie, ek weet julle kan [Hang in there, Kosie, I know you can].” As a sign of affection, he used to call me by the diminutive form of my name, but at that moment I was in no mood to appreciate it.

“But what if we don’t find the base? I mean, if it’s not there and we need more time?” I persisted, because I knew every step we made would be scrutinised by everyone in the unit. I sure wasn’t ready for failure.

He cut me short. “The base is there and you’ll find it.”

End of story. Hills was confident that the intelligence was accurate and that the “A-Team”, as he used to call us, would be successful.

“If you are compromised or you don’t find the base in six days, we’ll move in with the whole force. Then it becomes an area operation,” he said, but it was little consolation to the team. To us it was crucial that the base was located, but time was not on our side.

During our long vehicle infiltration, Da Costa and I drove in the command group, sharing a Casspir with one of the two unit chaplains, Padre Thinus Riekert, as well as some of the intelligence staff. Thinus was a deeply religious man but also an enlightened individual. We had many long, interesting conversations on the road and came close to solving the world’s problems with our infinite wisdom and insight.

After four days of travelling, the whole force arrived at the UNITA forward base from where both the reconnaissance and the attack would be launched. The UNITA base commander was clearly not happy with the large force moving into his territory, as it could compromise the position of his base – especially considering that it was within 80 km of Menongue airfield, where FAPLA had a squadron of MiG-21s. But he must have received instructions to accommodate us, and to this end did his best to please the South Africans.

Da Costa and I didn’t waste any time. We made a final comms check, packed our kit on one of the Unimogs and said our goodbyes. I drove with the team leader on the first vehicle and navigated on a bearing straight towards the target area. After 20 km we stopped. It was just short of last light. So far we hadn’t seen any tracks. We got off and the vehicles immediately turned around and left on their tracks. We moved into the undergrowth and waited for our eyes to adjust to the coming darkness. The noise of the Unimogs died away and all was quiet.

The moon was up and we decided to make good use of the available light, knowing that we were still far from the target. We covered a good fifteen kilometres, applying anti-tracking and movement techniques as much as the relatively fast pace allowed. When the moon set, at 02:00, we got a few hours’ sleep but dawn found us on the move again.

With the sun behind us, we decided to steal a few hours of daylight. We still hadn’t found any spoor and the bush was untouched. By mid-morning we decided not to push our luck and went into a hide. We settled into a routine of listening and watching. In the late afternoon we were rewarded with the first sign of the enemy – a series of explosions far to the west. I took a bearing and logged it, roughly drawing the direction on the map.

Again we decided to use some daylight, but this time we had the late-afternoon sun against us. As this was very dangerous, we decided to wait until the sun had set behind the tree line. Nevertheless, we made good time and went well into the night by the bright and beautiful moon. Early the next morning we were up and moving. We soon found some old SWAPO tracks, probably from a hunting party, and decided to don our anti-track bootees. By mid-morning we were in a hide again.

Before long we again heard continuous explosions. “Mortar practice…” Da Costa whispered.

Again I took the bearings and logged them on the map. As long as the enemy was there, we’d certainly find them.

In the heat of the day I crawled over to Da Costa to discuss our approach. The plan was to move at an angle towards the target area, logging the sound of explosions as we approached. We would keep moving until we had passed the suspect area. Only once we had a reasonable grasp of the base’s location would we turn and start moving towards it. We would start the final approach only as soon as we knew the exact location. I tried not to think of a penetration yet. That was the dangerous part – and hopefully would not be necessary.

By the third evening I was certain that we were close. We had located fresh tracks, all leading towards the suspected target area, and we occasionally heard the distinct crack of AK shots. That night we kept moving northwest on our bearing, past the area we now knew was the hot spot. In the early evening we heard vehicle movement for the first time. I duly took the bearing and logged it.

Bingo! Right direction. Right distance.

At first light the next morning we were hidden away in a thicket, backpacks camouflaged, food and water handy for the day, antenna up and the radio prepared. At any time now we could expect a security patrol or a hunting party to come by. We knew from experience that the stationary person had the advantage. In the flat savanna terrain, with its occasional thick undergrowth, a man on the move was invariably the first to be seen – exactly why an area reconnaissance in the bush was so difficult.

There was no high ground to establish an OP. Climbing a tree would be counter-productive, as you would just have tree canopy all around you – and in the process expose yourself to early-warning posts. You would be the intruder in a world the freedom fighter knew intimately. You would most likely approach from a direction he had determined – by the position he had chosen for his base. He would have arcs of vision (and of fire) across a chana or flood plain he had picked and prepared.

The fourth day passed slowly and, for me, extremely stressfully. Because of the uncertainty and the urgent need to locate the target, I found it difficult to pass the time. We slept in turns, albeit briefly and fitfully.

We had two days left to confirm the location visually, do a close-in recce and get back to the main force. I found some consolation in the big man’s relaxed demeanour. He seemed unfazed. I prepared a message detailing our finds of the day. Da Costa, lying on his side next to his radio, went through the ECCM procedures and transmitted the message.

There was also a message for us – from James Hills: “UNITA getting restless. Have to move in 2 days. Skuimbolle. JH.”

Literally translated, skuimbolle means “foam balls”. It refers ostensibly to the foam produced between the buttocks of a horse when it pulls a cart. This was Hills’ way of saying we should get a move on.

That night we swung from our original northwesterly bearing to a direction due west, certain that we had passed the base area. We went slowly. The moon was slightly from behind, giving us a minor advantage in case anyone might be stationary in front of us. It was painstaking work, moving from shadow to shadow, anti-tracking with every step, constantly communicating with the other. After covering about three kilometres, I was certain that the base would be directly south of us. We stopped and conferred.

Da Costa agreed. This was it; we could start the approach. “But I think we should take the backpacks,” he said. “We are not close enough yet.”

We decided to move with the packs until the moon had set. In the early hours of the new day we would approach with combat webbing only.

Once the moon was down, we stashed the backpacks and wiped out all signs of our presence before venturing out to locate our target. We used first light to gain a few hundred metres, encountering numerous tracks and cut-off trees, but no SWAPO. Soon we realised that there was no way we could approach the target in daylight, as the undergrowth was becoming too sparse. We went down and, after conferring quickly, decided to go back to the packs.

Back at the hide we crawled in close to the kit and covered each other up, readying ourselves for another long day. As the day dragged on we had a lot to log, again plotting everything we heard on the map. We were close – if only they didn’t find us first!

During the late-afternoon sched we reported that we would be going in close that night. Again we received an urgent message that the main force had to get moving the next day. After last light we kitted up and slowly closed in on the area where we believed the base was. By now we were patrolling at a snail’s pace, working our way due south. Following a technique we called caterpillaring, Da Costa patrolled a few hundred metres forward in light order, and then returned for his kit. We would then both move forward with the packs to his last position and put them down, after which I repeated the routine.

By midnight we still didn’t have any sign of the base. I was becoming concerned. Had we passed it too far to the west? Or were we still on the eastern side of it?

We took in a hide and tried to work out where we’d gone wrong. “Where is the river line where they are supposed to get water?” Da Costa asked, voicing my concern. “And the road that runs through it?”

“It must be further south,” I said. “They must get their logistics from somewhere…”

Time was running out and we did not know which way to move. I made the call to cache our packs before first light and move out in light order, firstly south and then due west. In this way we should find either the road or the river.

With the first faint light of dawn we were moving, deliberately now. Our eyes were piercing the half-light, and both of us knew that first light was a bad time to walk slap-bang into an enemy base, as soldiers tend to be exceptionally alert at this time. Sound and smell travel far…

We saw it simultaneously – the road running east–west in front of us. While crossing it through a thick patch of undergrowth, we noted three fresh tracks going east, probably to an early-warning post. Away from the road we swung west, and soon came upon the flood plain of a river. My heart was pumping. This was it – the junction of the river and the road, the flood plain across which their arcs of fire would be trained. I looked at Da Costa, and he indicated with a nod that he agreed.

But there was no way of crossing the open area in broad daylight. We went down and started crawling in the short grass towards the river line. Suddenly Da Costa stopped and pressed himself further down into the wet grass, the thumb of his left hand pointing downwards in the classic sign indicating enemy presence.

From the tree line across the river a SWAPO patrol of five or six men emerged, apparently not suspecting anything, as they casually started patrolling along the river line to the south.

Da Costa cupped his left hand behind his ear, indicating to me to listen. But I had already heard the commotion among the tall trees from where the patrol had appeared. I could distinctly make out laughter, a vehicle door slamming and orders being yelled. For some time we just lay there, trying to judge the size of the base by the sounds we were hearing. Occasionally we dared to sneak a peek across the open chana, but we were too low to see into the shaded tree line.

After a while I indicated to Da Costa to move back, as we could also expect a patrol on our side of the river. To get any closer, we needed to approach the target from a different direction.

Slowly we crawled back into thicker bush, making sure not to leave any drag marks on the ground that was still wet with morning dew. We backtracked the same route to our packs from where we moved out a further two kilometres to make comms.

My message was short and to the point: “Base found. Enemy. Number unknown. Need one day and night to confirm.”

James Hills’ voice came on the air. He obviously didn’t bother typing a message: “Negative. Negative. No time. I need you here tomorrow morning. We are moving tomorrow.”

Da Costa and I exchanged glances. No time for a close-in recce? Tomorrow morning? Sixty kilometres to go? Enemy all around? This was a tough one.

I tried once more, a brief message to confirm that we had found the base, but needed time for confirmation. But that was it. The colonel maintained that they couldn’t wait any longer. Time was of the essence. Later he would explain his decision: they had good reason to believe that some of the UNITA elements were in contact with SWAPO, and that our intentions could become known to the Eastern Front HQ at any moment.

The call was made. We would head back and make the best of the situation. For another kilometre we remained vigilant, moving from cover to cover, constantly checking our backs, changing direction and anti-tracking. Then we increased the pace. By first light the next morning we had covered 30 km, and requested a pick-up in the same area where we’d been dropped. Just to make sure the 5 Recce guys did not confuse us with SWAPO, I took off my shirt to expose my white upper body. By mid-morning the Unimogs drove into the RV, and it was a huge relief to see their smiling faces.

In the camp we found 5 Recce preparing for war. Weapons were being cleaned and oiled, vehicles refuelled from the bunkers, camouflage nets pulled tight, food and water secured. The intelligence guys had already drafted a sand model; we just had to fill in the details.

Colonel Hills called all the commanders in for a quick debrief before issuing orders. I ran them through the events of the previous days and described the location of the base, drawing the road and the river line on the sand model. On the map I plotted a six-figure grid reference of where I estimated the centre of the base to be.

Then came the questions.

“How many are there?”

“Did you see any bunkers?”

“How big is the base?”

“What weapons do they have?”

Da Costa and I covered what we could, but in the end the information, from the attackers’ perspective, was sketchy. Finally one of the commando leaders asked, “Are you sure the base is there?”

“The base is there,” I said sternly, “at that grid reference. With vehicles and a lot of people.”

Then one of the commanders asked Colonel Hills, “So what happens if the base is not there?”

“Then 5 Recce will have a new transport park commander,” the OC joked, perhaps in an attempt to break the tension. I was quite amazed that they doubted us – after all our trouble to locate the base. We’d even been ordered to return before we could do a close-in recce.

“The base is there,” I repeated. “I’d put my life on it.”

Dave Drew gave a quick intelligence update, explaining the location of the base and the approximate size. Then James Hills briefed us on the attack. The plan was straightforward. That night I would lead the two stopper groups, 51 and 53 commandos, as well as the mortar platoon, in on the actual line of attack – on foot. Along the route in we would mark the axis of advance with toilet paper to ensure that the main force got to the right position. Once at the forming-up point, exactly three kilometres from the target, we would leave the mortar platoon to deploy in a clearing next to the east-west track. Then we would break away from the attack axis and navigate to a position two kilometres north of the target, where 53 Commando would deploy as a stopper group. This navigation would be by dead reckoning (DR), relying on bearing and distance, as there were no outstanding features in the flat terrain.

Once 53 Commando was in position, I would then navigate to a position three kilometres west of the target, leading the men from 51 Commando to their cut-off position along the east–west road, where we would wait in ambush for any fleeing cadres.

The assault force – regimental HQ, 52 Commando, a company from 101 Battalion, as well as elements from 2 Recce (the Reserve Force contingent that had been called up for the operation) – would follow just before first light. Da Costa would do the navigation to the forming-up point.

The assault force would form up and advance to contact. At first light, as the attackers reached the river line, the mortars would open fire to soften up the target. Then the attack would commence. It seemed straightforward enough.

Before last light that evening, we started moving out. The vehicles took us to within 20 km of the target. Then we set out on foot, found the east–west vehicle track and made good time. By 02:00 we were at the forming-up point. The mortar platoon deployed and set their weapons to fire at the six-figure grid reference I had given as the centre of the base. We marked the forming-up point and the axis of advance with toilet paper, then set out on a bearing to 53 Commando’s position, circumnavigating the target area. This was pure DR navigation, as there were no features to guide us, but I was confident that I had led them to the right position.

We set off for 51 Commando’s position to set up an ambush west of the target. The men were deployed in an extended-line formation next to the road, facing north, the only cover a termite heap behind which the RPG gunner lay. We waited, listening on the radio as the assault force formed up and started their advance to contact. By first light we could actually hear the vehicles, but the order never came for the mortars to open fire.

Then the voice of one of the commando OCs came on the air, “There’s nothing here… No movement. Do you think we have a new transport park commander?”

The response, “Nothing here. It’s a lemon. Sure we have a new –”

Then all hell broke loose.

A DShK 12.7 mm deployed in the ground role created havoc as it covered the eastern entrance to the base. In the opening shots of the attack one of the 52 Commando Casspir drivers, Corporal ML Mashavave, was killed. In the meantime, 53 Commando, having advanced further south because they could not detect any enemy activity, had to withdraw out of the line of fire, missing the opportunity to cut off some of the cadres who were fleeing directly north.

Luckier was 51 Commando. A peculiar-looking SWAPO command vehicle came careening down the track and erupted into a ball of flame as the RPG rocket found its target and bore down on the poor RPG gunner behind his termite mound. Literally centimetres from the frightened man’s face it came to a standstill, half-suspended over the mound.

Seconds later a Gaz 66 truck followed. The RPG gunner, probably still in a state of shock, missed the target, but two operators with SKS rifle grenades planted themselves in the road and stopped it in its tracks, while the rest of the operators blasted away at the driver and passengers.

It turned out that there were a comparatively small number of enemy in the base, as the majority of the cadres were at the rehearsal area twelve kilometres further west. When the attack commenced, the SWAPO HQ and protection element, realising that the attack force was far superior, decided to flee. Thus only a limited number of cadres were killed. Later that morning, as I was sitting in the centre of the base at a bunker that appeared to have been the command centre of the so-called Eastern Front HQ, Captain Robbie Blake, the 51 Commando intelligence officer, drove up in his Casspir, got down and handed me a slip of paper.

“What’s this?” I asked, wondering if there was another target.

“It’s an eight-figure grid reference from the SATNAV (a satellite navigation system and forerunner of the GPS),” he said. “Looks like you were right. It’s the position you gave us.”

I checked my map and realised that the grid reference corresponded exactly with the position of the base I had conveyed to the OC the day before.

In the meantime 52 Commando had reorganised and driven west to engage the rehearsal area. They were ambushed by a large SWAPO force hiding in thick bush on the side of the road, but managed to swing the vehicles into combat formation and fought straight through the ambush site, killing seven enemy. Throughout the rest of that day the three commandos were engaged in follow-up operations. Numerous contacts ensued and a total of 39 SWAPO fighters were killed.

That afternoon, during an ambush laid by more than 100 SWAPO soldiers, Corporal Andr? Renken was killed instantly when 2 Recce’s Casspir was shot out with an RPG. Throughout the day a few operators from 5 Recce were wounded, mostly by shrapnel, and had to be evacuated by helicopter.

Renken and Mashavave were the only South Africans killed in the operation. Mashavave’s body was flown back after the initial attack (the combat zone had to be cleared before the helicopters would approach for the pick-up), while Renken’s remains were placed in a body bag and transported in our Casspir. The high spirits Thinus Riekert and I had felt on the inward journey were gone. As soon as the convoy reached an area considered to be out of the immediate threat of the MiGs from Menongue, the Pumas were called in to take the remains back to Oshakati.

The convoy took another four days to reach Oshivelo, where an extensive debriefing took place. The operational vehicles were driven back to Phalaborwa in convoy, while the commandos were trooped back by C-130.

While the reconnaissance for Operation Colosseum was one of many recce missions I participated in, for me it determined future modus operandi. The mission set the trend for a phased approach to locating an enemy base in the bush – initially through continuous reporting of noise (this while approaching the suspect area at an angle and passing it at a distance of three to four kilometres), then building a picture from visual signs, and finally from a close-in reconnaissance. Later, Da Costa and I analysed the sequence of events meticulously and compiled a textbook for specialised reconnaissance missions based on the actions taken during those few days.

In subsequent years, after the first democratic elections and the integration of erstwhile opposing forces, Da Costa, then a senior warrant officer at the Special Forces School, became instrumental in training young operators and establishing Special Forces doctrine. As a role model for aspirant operators over the years, he has exerted immeasurable influence and played a major role in shaping the lives of so many young men.