9

Three Crosses at Lubango:

Operation Abduct 2, November-December 1987

“Where there is much light, the shadow tends to be deep.”

WE DEPARTED FOR Ondangwa on a regular scheduled SAAF flight. Although we wore standard-issue bush hats and tried to blend in with the rest of the crowd flying to the war zone, we still stood out like sore thumbs. For one thing, Jos? da Costa’s huge frame was hard to miss, and, for another, the Recces always “hid” their weapons in non-standard (but very obvious!) rifle bags. Even the bags used by Special Forces soldiers were different from the regular army’s balsak. Special Forces soldiers often took the scheduled flights to and from Ondangwa, and so Recces were a fairly regular sight.

Operation Abduct 2

Oom Boet and the Tac HQ team had departed by road to Ondangwa two weeks before the deployment. On our arrival we found the Tac HQ at Fort Rev in the usual predeployment frenzy. The most important task that remained for the team was to brief the Tac HQ, as well as the pilots and the “back-up” team on the emergency procedures and E&E plan. Before this could be done, the team had to work through the emergency procedures, escape routes and rendezvous (RV) points to ensure that each one understood and memorised every single detail and, more importantly, that each procedure and each action had the same meaning for all three of us. The E&E plan the Tac HQ would implement if anything went wrong was then meticulously drawn on a map overlay.

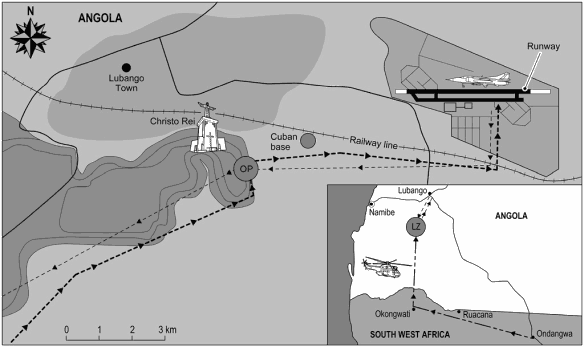

We had decided on a landing zone (LZ) 60 km south of the Lubango airfield. The team would deploy by rappelling from the helicopters onto the highest mountain ridges, where we would establish a cache and observe the area for two days. Fighter jets would act as an escort for the helicopters. Because of the distances involved and the dangers of flying into an area where the enemy had air superiority, the fighters were also assigned the job of telstar should there be a communication breakdown or any other emergency. The back-up team, made up of Special Forces soldiers from 51 Commando, would deploy to the last known location of the team should the E&E plan be activated.

We would take the normal large Small Team pack for the infiltration, and switch to the pack designed for the explosives on the night of the penetration. During the final inspection our equipment was once again thoroughly checked and scrutinised for non-traceability. Not one single piece of equipment could be linked to South Africa. Then each operator handed his Captured Info document to Oom Boet for safekeeping, the contents securely committed to memory.

Our choice of weapons was, as always, meticulously planned: I would carry my trusted Hungarian AMD and silenced pistol; Diedies had a silenced BXP and a pistol (without silencer); and Jos? da Costa took a normal AKM (the modernised version of the AK-47) and a Russian-origin Tokarev pistol. Since I was doing the navigation on the route in, I would be armed with a non-silenced weapon – to work in our favour during an initial engagement. We knew from experience that silenced weapons did not hold the enemy’s heads down, presumably because they did not realise they were being shot at. Likewise Da Costa would have a non-silenced assault rifle for support fire. During the penetration, Diedies would lead with the silenced BXP, ready for initial contact. If I had to do a stalk on an aircraft, I would approach with the silenced pistol and keep the AMD on my back for firepower in case we needed to fight our way out.

Our lunch before the deployment was a lavish spread, and a cheerful atmosphere reigned. Boet Swart proposed a toast to the “conquering” of Lubango. He joked about the packs being bigger and heavier than the operators themselves.

“Small team, big pack, small brain…” he said, as so many times before. “I’ll never understand the small minds of the men with the big packs. They could have all this wonderful food, a warm bed to sleep in, pretty girls, and yet here they are off into the bush again…”

The huge packs were loaded onto the choppers on the hardstand before start-up. Both helicopters had been prepared for rappelling, and the A-frames had been fitted in a closed hangar the night before. The system used for rappelling from the Puma at the time was a frame that fitted into the helicopter, with extension arms that contained the anchor points for the ropes. The frames were intended to prevent excessive external force on the superstructure of the aircraft. The plan was for the operators to rappel down first, after which the heavy packs and cache equipment would be lowered by a pulley system.

At 14:00 the Pumas, each with two additional ferry tanks mounted on the inside, had taxied out and waited for us in front of Fort Rev. We flew to Opuwa in the Kaokoland, where the helicopters had to refuel. I tried to sleep on the way, but was too excited.

This deployment was the one we had been living for; it was a textbook Small Team operation. To me it felt as though we had spent a lifetime preparing for Lubango. The very name of the place had a mysterious ring to it. Strangely, a deep and profound calmness had come over me, and a determination I had not quite experienced before. I visualised how we would fly back in the same helicopter a month later – having achieved success. I had a distinct vision of how we would approach the target and work our way from aircraft to aircraft.

This new feeling did not at all mean that I was not afraid. I did not have a death wish, nor was I under some wild delusion that we would rush in and show everyone how it was done. After weeks of meticulous planning and preparation, the sessions with Johnny and the few days I had spent alone along the Orange River, I felt content and at ease with what lay ahead.

While we waited for last light, Oom Sarel shared the customary communion with us under a cluster of trees. His message took me back a few years, to the moment before my very first Special Forces deployment with 53 Commando at Nkongo, when he had built mountains in the sand to explain the meaning of Psalm 125:2: “As the mountains surround Jerusalem, so the Lord surrounds His people now and forever.”

He made this verse applicable to Lubango, and reminded us that, as the mountains surround the town to the south and west, the Lord is always there, with the only difference being that He completely surrounds us. Oom Sarel’s message was simple and to the point and added to my sense of calmness and determination. Never before had the wine and bread had such a tangible meaning for me as on the eve of our deployment to Lubango, when I shared it with my comrades and Oom Boet.

After the short service I asked Diedies how he felt, knowing full well that his priorities had shifted now that he was a married man. But if I had forgotten the iron will and unique fibre of the man, his big smile and quick answer reminded me promptly. “Camels don’t cry, Kosie,” he said, referring to the motto displayed on the 52 Commando logo. I knew Da Costa was okay; he was as solid as the very mountains around Lubango.

Just before last light we received a message that the jets were airborne for their top-cover job. We flew straight from Opuwa to the border and crossed the Cunene River in the area west of Swartbooisdrift, then nap-of-the-earth towards the LZ, following the valleys and depressions of the rugged southwestern Angolan countryside. Diedies, Da Costa and I were in the first chopper, along with the two dispatchers. The packs and the bulky cache equipment were in the second one, with two dispatchers ready to let the equipment down by pulley.

Three minutes from the LZ the doors were opened and the struts from the A-frames pushed out. We hooked up to the anchor points and got ready to swing out onto the steps. After orbiting the LZ area once, John Church, the lead pilot, approached a protruding rocky ridge and eased the aircraft into a hover. On the dispatcher’s command I swung out onto the steps, with Da Costa following behind. As I was about to launch, I felt the dispatcher’s hand on my arm and saw his outstretched hand in a “don’t go” gesture. The next moment the helicopter lifted off and we started flying from outcrop to outcrop, looking for a smoother surface on the rugged mountaintop.

But I was in trouble. Da Costa, who was on the strut in front of me, was pushed against me by the rush of the wind. I held on to the rope for dear life, but felt it slipping slowly from my grip. I pulled the loose end around and tried to hold it down tightly against my body with both hands to improve the friction on the descending device, but slowly and steadily it slipped. Da Costa’s massive weight, compounded by the wind rush, was now squarely on me, and my cramped hands couldn’t hold any longer.

After what felt like an eternity, the aircraft reduced speed and slowly moved into a hover. It was not a moment too soon. Without waiting for a signal, I let go, and had to use both hands to control the rope as I descended slowly onto the rocks below.

Da Costa followed, while Diedies had already touched down after descending from the port door of the helicopter. The second helicopter, carrying the equipment, moved in. The three of us received the packs at the bottom, unhooking the karabiners as they touched down. When I received my pack, I realised its frame had broken under the weight of the kit. As prearranged, I gave the rope three fierce tugs to inform the dispatcher that we needed a spare pack. For some reason there was no response and the helicopter took off. As the aircraft moved away and the noise subsided, we informed the pilots that we needed another pack. However, since they had been circling the area considerably longer than planned, they thought it better not to return for fear of giving our position away.

This left us in quite a predicament. The frame of my pack was completely shattered, and the only alternative was to use one of the much smaller packs from the cache. I packed the explosive charges, night-vision goggles, as much water as I could force in and some of my rations. The rest of the food was shared between Diedies and Da Costa.

We used the rest of the night to cache the extra food, water, batteries and a radio. Since we were quite high on a rocky outcrop, we considered it safe to stash the kit in hollows among the rocks. After first light we sterilised the area, checking that the outcrop was free of tracks, everything was hidden and the vegetation restored to how it was before.

For the remainder of the day we remained on a nearby peak, watching the cache area and the valley below. Except for dogs barking and a cock crowing in the distance, it was quiet. We didn’t see any people, nor did we hear any vehicle or aircraft movement, so we decided not to waste any time and to start moving that night. Even though I had strapped some extra water bags onto my rucksack, I was still carrying much less weight than Diedies and Jos?. I took the lead, navigating along the mountain ridge leading north towards Lubango. It was hard, meticulous work, as I had to find the easiest route in the rugged terrain, all the time considering my two heavily laden comrades, but at the same time keeping high enough up the mountain slopes to avoid the areas where people might find our tracks.

By first light every morning we moved as high as possible up the mountainside, carefully picking our hide in thickly vegetated or rocky spots to ensure we stayed off the beaten track. After we had settled down on the slope, I would take a day pack and move to the top of the mountain ridge, from where I could keep a better lookout and at the same time plan the route ahead.

The infiltration did not go without incident. Late one afternoon while waiting for the sun to set, we watched an old man armed with a bow and arrow walking straight through our hide, not looking left or right. To this day I don’t know if he saw us, but we soon packed up and anti-tracked away from the area.

Another incident took us completely by surprise. Diedies was studying his map when a huge snake appeared out of the blue and sailed right across his lap. We must have been in its territory, for it whiled away the rest of the afternoon in Diedies’ company. Fortunately, our comrade was so stunned that he could not move, and just watched the snake until it eventually disappeared into a hole.

As we closed in on the target area we passed a plateau with spurs sloping down to the savanna below. Early one night we were moving past one of these ridges when all of a sudden we heard music high up on the mountain. We moved into cover, took our packs off and listened to the noise. It gradually grew louder and we soon became aware that it was the sound of a group of men singing in harmony. There was a fence line running down the mountain straight towards us, and we realised that the singing voices were moving towards us along the fence. We ducked into cover and waited.

A group of about twenty men appeared, singing a touching song about the ANC martyr Solomon Mahlangu. It was the same song I had heard during the Know Your Enemy course as part of my Special Forces training. Listening to those beautiful men’s voices in the still night air, singing a song that, to me, was completely out of place deep inside Angola, was a strange and quite moving experience.

The men were passing barely ten metres from us when, suddenly, one of them jumped over the fence and ran towards the cluster of bushes where we were hiding. The singing died down, as everyone waited for their comrade, who stopped close to our hiding place. The sound of a bowel movement shattered the silence as he took a crap almost in our faces. The rest of the “choir” burst out laughing, making funny comments about the man’s running stomach. We literally had to clamp our mouths shut not to join in the laughter.

Soon the stray soul rejoined the group and the singing resumed. We listened in stunned silence until the sound eventually faded away far down the mountainside. Then we finally gave in and laughed until we could no more.

That night we had yet another strange experience. We had moved down a depression into a thicket where we wanted to grab two hours’ sleep before establishing an OP for the day. Just as we had taken off our packs and settled down, Da Costa jumped up with a muffled scream. Diedies and I grabbed our weapons and rolled around into cover behind our packs. I quickly realised what was happening when I felt the sting of ant bites all over my body. Unknowingly we had bedded down in the path of a colony of killer ants; by the time we realised it, they were all over us – into our kit and under our clothing.

Da Costa was dancing around like a madman, ripping his clothes off and slapping the tiny creatures from his body. Diedies and I soon joined in, but then realised that our efforts were fruitless, as we were still in the colony’s killing zone! With no regard to tactics or silence, we grabbed our garb and gear and moved to “safety”. After testing the ground a few times – in a very literal sense – we found an antless spot, and took our time to remove our clothes and shake out the little beasts. For days after that, right up until we reached the target area, we still discovered ants in our kit.

One evening when we were about 20 km from the target, passing through the Huila district, we decided to make up some time by moving barefoot on a sandy pathway running along our bearing. It was pitch dark – ideal for the penetration. Once again I took the lead, walking without night-vision goggles, weapon at the ready, and relying on my senses to pick up any sign of people approaching. Diedies followed with the night vision, using it intermittently to detect sources of light such as the embers of campfires. Da Costa brought up the rear, cautiously checking behind for anyone who might be catching up on us.

Smelling rather than seeing the vegetation, I realised that we were passing a built-up area with bougainvillea along its fence line. It turned out to be a Roman Catholic mission. As we passed a gate in the walled perimeter, Diedies pulled me by the sleeve and handed me the night-vision goggles, indicating that I should look at the wall. The eerie green light of the night-vision equipment revealed a larger-than-life statue of Christ. It was almost like a vision, and the three of us moved off into the night, the image clearly imprinted on our minds.

Before first light we were atop the mountain overlooking Lubango, where we had planned to spend three days watching the area and building up a picture of the target itself, the routine, best infiltration route and escape routes. But we were in for an unexpected and unpleasant surprise: the whole mountain had been stripped of undergrowth, leaving no cover for us. We also discovered smouldering moulds used by the local population for the manufacture of charcoal. What we hadn’t realised from the aerial photos was that the lower brush had been removed to feed the smoking coal ovens. The tree canopy shown in the photos had suggested that it was a thickly vegetated area, but the reality on the ground was vastly different.

We were in trouble. We searched frantically for any kind of cover, but the mountain offered nothing. It was now broad daylight and we had nowhere to hide. Below us we could hear the buzz of the town as it awakened to the new day. In the distance we could see aircraft activity on the airfield. Finally we decided to lie down in a slight depression and wait out the long hours. We covered the kit as best we could. Diedies got up into a tree, while I made myself small between two packs. Da Costa, who had a Cuban peaked cap and FAPLA officer’s insignia, would act as our deception.

Before long we could hear people coming up the mountainside, and soon groups of women and children swarmed across the open terrain in search of more vegetation to destroy. Da Costa and I made ourselves as small as possible, and managed to survive until mid-morning when two women with a string of children in tow walked straight into our hide. Da Costa had no choice but to get up and wave them away. They got such a fright that they dropped their bundles there and then and started running down the mountainside, howling.

This created a stampede, as the children tagged along screaming, not exactly knowing what the threat was. Da Costa ran after them and shouted for them to come back, trying to calm them down. But the damage was done. The whole bunch disappeared down the mountain in the direction of the FAPLA base at the bottom.

It was time for action. If we were caught in the open terrain we would be in serious trouble. We decided to withdraw deeper into the mountain and look for better cover. But first Diedies ordered me to take pictures of the target area from the tree. I climbed the flimsy branches of the tree as high as I could and took a panorama of the airfield and the military bases below. Then we gathered our gear and moved in a westerly direction, taking care not to leave any tracks.

After about two kilometres we came unexpectedly upon a shallow valley with a thickly vegetated river line, where we found a thicket of bamboo reeds to hide in. It was isolated cover, offering no escape routes, but it was the best we could get. We carefully anti-tracked past the thicket and then doglegged back into it. For an hour we kept vigilant watch on our track and listened for signs of a follow-up.

During the morning sched we informed the Tac HQ of our predicament. Boet Swart reacted promptly and sent a message that we should not take the risk, as the odds were clearly against us. However, he asked Diedies to make another sched in the afternoon, as he needed to consult with Pretoria before giving us a final decision.

We considered our situation and weighed up the pros and cons, contemplating whether the enemy would be on the alert and waiting for us. Our instincts told us the job was impossible: we would have to infiltrate a further seven kilometres through a populated area to the airfield, dodging numerous deployments of soldiers to get to our target, and then still penetrate the airfield defences to get to the fighter aircraft. Time would become a critical commodity.

A further challenge, now compounded by the lack of cover on the mountain, was the problem of getting out. We tried to work out a time schedule and a route from the target to the nearest cover. Now that we had seen the target area, we realised that we needed at least two hours under the cover of darkness to get to safety after laying the charges, which meant that we had to finish the job by 03:00 in the morning. This was cutting it fine, as we only intended to penetrate the perimeter by 01:00.

We discussed our options, knowing we could no longer watch the target for a few days as initially planned, because we did not know whether the women had reported us to the enemy or not. Finally we came to the conclusion that we would have to penetrate that night, against all odds. At least we had had a glimpse of the area and would be able to navigate accurately to the point of entry.

In the afternoon, during the final sched, there was a message from the GOC himself, who told Diedies to use his discretion, while reminding him that it was not worthwhile losing an operator, as it would have international consequences. This message increased the pressure on us; responsibility for failure would be placed squarely at our feet.

Finally, late in the afternoon, Diedies called us together again and said, “Hey, guys, there’s only one way. We came here for a reason. What are we waiting for?”

Both Da Costa and I had also made up our minds by that time, and the job was on.

We decided to move the timeline forward to gain a few extra hours. By 16:00 Diedies and I started to prepare our penetration packs. We armed the charges and placed them in their individual pouches. Each of us had a water bag and emergency rations in the central pouch, together with the “Vernon Joynt glue” to stick the charges to the aircraft fuselages. Then we donned our penetration gear: the regular chest webbing with pistol; essential survival gear and emergency kit; Tacbe-499 radio beacons, strobe lights and infrared torches; sheepskin covers for knees and elbows; and night-vision goggles on the chest. I rounded off the picture with an Afro wig as headdress tied to my shirt.

Before last light we cached the packs in the bamboo thicket and made our way to the side of the mountain where we had ascended that morning. Da Costa moved along with a daypack and the HF radio. The plan was that he would stay on the highest point of the mountain closest to the target. He would wait until first light the following morning and then, if he hadn’t heard from us by 06:00, move back into cover. The bamboo thicket would serve as our emergency RV for a full twelve-hour period. At last light the following night Da Costa would start his exfiltration along the E&E route. If nothing had been heard from us by then, the E&E plan would be activated.

We parted quietly, shaking hands and wishing each other well. It was still light enough to maintain a steady pace down the slope. Halfway down the mountain Diedies stopped me and pointed up the mountain to the west. Against the last red light of the setting sun, on the crest of the next mountain ridge, was Christo Rei, the statue of Christ overlooking the town. It was a most striking sight, and, had it not been for the harsh reality of what we were about to do, the view might have been as if from a dream. Looking back at the experiences of that night, it was indeed a significant moment.

We made good time and reached the railway line by 20:00, and then moved along the vehicle track next to it. Once a group of soldiers passed us from the front, but Diedies exchanged some brief greetings with them and they didn’t even bother to stop, obviously in a hurry to get to their destination. It was Saturday night, and we had bargained on some heavy partying among the various deployments of soldiers.

The Cubans were notorious for boozing and taking drugs, and the chances of them carousing with their FAPLA comrades were a hundred to one. Indeed, as we approached the Cuban base among the bluegum trees, we could hear loud Spanish music and drunken voices singing along. There was clearly a party on the go, and we decided to hang around and listen for a while. It was still early and we had to wait for the right time to penetrate. The merry mood continued, and we decided that the Cuban contingent posed no threat that night.

Following the railway line, we moved further east towards the target. At 23:00 we left the tracks and turned north on a bearing to the point where we wanted to cross the perimeter fence. I took the lead, as this was pure DR navigation and we needed to find the exact penetration point in the pitch dark. Furthermore, we needed to navigate accurately to the aircraft parked on the eastern apron of the runway, approximately 1 500 m north of the crossing point. Once the charges were placed, we would have to navigate back to the point of penetration.

We reached the perimeter fence by 23:30 and decided to stay put and listen for a while. Just as we had settled down, a patrol of six guards passed us on the vehicle track inside the fence line. They walked quietly, without talking, which meant that they would probably have picked us up had we started cutting the fence earlier. We gave them a few minutes to disappear and decided to cross before the next patrol came around.

During the rehearsals we had practised a technique in which Diedies would hold the fence down with his gloved hands while I did the cutting. This would prevent the taut wires from snapping with a twang that (as we knew from previous experience) could alert the whole of southern Angola. However, we soon discovered that the fence wire was not taut at all and that I could cut it alone – while covering the clipping noise with a cloth brought exactly for this purpose. Diedies moved back into the brush to listen for further patrols.

It was slow work, as each strand of cut wire had to be treated carefully. I did not want to make any noise, and the loose part of the fence had to be folded back and tied into position with the strands of cut wire to make it as inconspicuous as possible. By 00:30 the hole was ready, and we entered as quietly and as quickly as possible, careful not to leave any tracks on the ground. I folded the loose fencing back and tied it in its original position. In the dark it would pass as untouched, and we intended to use it as an escape in case of an emergency.

I navigated past some bunkers, possibly an ammunition store for the fighter aircraft ordnance, which we could not recall from the aerial photos. Once again I moved without the night-vision goggles, while Diedies scanned the night with his goggles to locate any sign of danger. I had my AMD at the ready, while Diedies moved with silenced sub-machine gun. We reached the hardstand by 01:00 without encountering any guards. Using the night vision, we could make out a MiG-21, barely 30 m away, crouched on the tarmac against the skyline, with the dark shape of another aircraft further off. We crouched down in the low bushes bordering the tarmac and quietly discussed our approach, as well as our escape route and emergency RV – which would be the hole in the fence where we had entered.

I would take the first aircraft, and then we would work our way down the line of fighters along the tarmac. We decided against the initial option of splitting up to reach more planes in the shortest possible time; in the darkness it was impossible to determine separate lines of targets for each operator.

Silently, with deliberate, slow movements, I slid my pack off and took out the first charge, together with a set of glue tubes. With practised fingers I undid the straps of the pouches and arranged the rest of the charges so they would be within easy reach. I felt strangely calm and ready for the task at hand. The overwhelming fear I had experienced in the past was absent. Instead, a sense of sheer dedication to get the job done had taken over. Deep inside I knew that I was exceptionally well prepared for this, and that the stakes were too high to fail.

Diedies positioned himself on the edge of the tarmac to listen out and warn me if anyone approached. Quietly, I slipped the charges back on and draped my AMD in a fireman’s sling down the centre of my back to allow freedom of movement. Then I started the stalk towards the aircraft, silenced pistol cocked and ready in the right hand, charge in the left and night-vision goggles on my chest.

Ten metres from the aircraft I stopped to observe with the night-vision goggles. The darkness of the night was absolute, as we had hoped, but it also meant that I could not see below the fuselage. Not even with the beam of the infrared torch could the night-vision goggles penetrate the complete blackness under the belly of the MiG-21.

The night was dead silent. There was no sound from underneath the aircraft, nor could I make out any shape under the belly. I realised I needed to go lower to observe better. Slowly, and as quiet as a mouse, I eased forward to move into the blackness under the fuselage so I could look up against the ambient light of the sky.

I crouched to move in under the wing.

Then a voice pierced the silence of the night from the darkness underneath the plane. My worst fear was coming true.

“Quem s?o voc?…?” The voice was hesitant at first, restrained with fear.

Then stronger: “Quem s?o voc?? [Who are you?]”

Then the all-too-familiar cocking of a Kalashnikov shattered the fragile night air, barely three metres away under the belly of the aircraft, cracking like a rifle shot in the darkness.

As so often before, I was confronted in the pitch dark with the penetrating, nerve-racking sound of an AK-47 being cocked in my face as I crept around in an enemy base. This time I also felt exposed against the night sky on the open tarmac. My own weapon was slung on my back; the silenced pistol in my hand was of no use if I couldn’t even see my adversary.

The guard’s voice now became bold and challenging: “Onde voc? vai? [Where are you going?]”

A second AK was cocked as if to bolster the challenge.

The long hours of rehearsals during those dark nights at Hoedspruit Air Force Base kicked in – instantly and instinctively. In a split second I had covered all the options in my mind – the shortest route to safety, the best course of action in case of white light, the most effective way to present myself as the smallest target possible. I mumbled drunkenly in Portuguese, automatically recalling the phrases we had rehearsed so often: “Companheiro, o que voc? faz…? [Comrades, what are you doing…?]”

At the back of my mind, I knew from previous experience that they would not open fire immediately. I knew my enemy was scared and uncertain. They could not see me clearly and had no idea who I was. I had to move now.

This was my only chance.

Keeping up my incoherent babbling, I pretended to stumble, and in the process ducked low down on the tarmac, reducing the clear target my silhouette presented against the skyline. Going low, I crawled back towards our RV, where Diedies waited anxiously. He had heard the encounter and was ready to move. We hurriedly discussed our options and waited for reaction from the guards. Although we could not see anything, we heard muffled sounds coming from the direction of the aircraft. Could we exploit their confusion and move round to the aircraft on the far side? Soon we saw movement against lighting in the distance, and then our minds were made up for us as a vehicle with a spotlight started moving along the tarmac in the direction of the hardstand.

We knew we had to get out of there. “The hole in the fence… We have to find the hole in the fence!” Diedies whispered.

I flicked the compass open and faced south to find the back bearing of our approach to the apron. As I fixed the compass reading and looked up at the night sky to find a suitable star, I saw the Southern Cross, or Crux. At that moment it was at the apex of its pathway through the sky, pointing vertically down and almost inviting us to follow it. We both looked up at the constellation of stars and realised it was the third cross in as many nights to make an unexpected but major impact on us.

It was strangely comforting – to follow the cross amid the commotion erupting around us. The enemy was now obviously looking for us, apparently strengthening their defences around the aircraft, as we could hear a number of vehicles moving into position. We moved quickly, following the Southern Cross and going low through the shrubs, once again avoiding the cluster of bunkers we had encountered earlier.

As we approached the perimeter, slowly and very quietly, Diedies again urged from the back: “You must find the hole, Kosie, we cannot cross over…”

We reached the road where the patrol had passed by earlier, but the reaction apparently hadn’t reached this far. In the direction of the tarmac we could hear vehicles and voices as the enemy started coordinating their search. I brought my gaze down from the Southern Cross, and suddenly spotted the hole in the fence right in front of us, squarely on our bearing.

We wasted no time in getting through to the relative safety of the brush outside. In a matter of seconds we had passed through and soon were back at the railway line. Diedies insisted we sit down to reassess the situation. We were both immensely relieved as the realisation dawned how we had been led to a safe exit.

“What about the trains?” I whispered. “Shall we move along the railway line and blast some locomotives?”

Diedies didn’t even consider it for a moment. “It’s either the aircraft or nothing,” he answered. “We don’t want to spoil any future chances, and it wasn’t the aim of the operation in any case.”

For Diedies, second best would never do. The first principle of war – the maintenance of the aim – was non-negotiable. We either did the job we had come for, or we accepted failure. Much later, when we debriefed and carefully relived the operation, and once again weighed our chances of success, I realised how important was this principle. It would not have made sense to divert the focus to a lesser target with no bearing on the bigger war effort – especially in a situation where the defeat was tangible and the need to obtain some sense of achievement was overwhelming.

We moved quickly back along the tracks. With all the excitement we had not kept track of time, and we knew that we had to be out of the area before first light, as a search would certainly be launched. We once again passed the Cuban base, but this time it was dead quiet.

At the foot of the mountain we took a short rest. We scrambled up and tried to call Da Costa on the Tacbe. As we approached the point where we had left him the previous night, he suddenly answered, and we gave the “all clear” password. He appeared out of the darkness from under a tree and said he had been listening to us scramble up the mountainside, but was not sure whether it was own forces or not. After Diedies briefly filled him in on the night’s events, he had the same reaction as I did: wasn’t there any other target? Couldn’t we stick around and find something else to destroy? Should we simply turn back empty-handed?

There wasn’t any time to argue the point, and, even though it weighed heavily on our minds, we all knew withdrawal was our only option. Da Costa led the way to the bamboo thicket and we repacked our equipment after disarming the charges. He then set up the radio while we sorted out our kit. Dave Scales responded immediately when Da Costa sent the familiar clear call in Morse. He had clearly been sitting by the radio the whole night. Amazingly, despite the odd hour, we had a full signal.

Dave asked if he should “pull” us, triggering the two radios into frequency-hopping mode. Da Costa responded with a “dah-dit, dah-dah-dah” – meaning no. Dave then wanted to know if everyone was okay and whether we were together, to which Da Costa responded in the affirmative. Then came the question everyone at the Tac HQ anxiously wanted an answer to: “Successful with your enterprise?” To this our man answered with a very deliberate “dah-dit, dah-dah-dah”.

After asking a few more questions Dave was satisfied that Da Costa was not communicating under duress. He understood that we were moving out and that the next sched would only be by late afternoon.

We donned our anti-track covers and moved out in a southwesterly direction, still deeper into the mountain. I set a fast pace, as we wanted to clear the immediate area where, in the morning, the enemy would likely search with helicopters. Every now and again we encountered small villages or farmsteads in the valleys, which we took care to avoid.

Where the terrain allowed, we spread out and anti-tracked as well as we could, considering the speed of our retreat. At some point we passed beneath a cluster of trees in what appeared to be some kind of an orchard. The familiar smell of fresh guavas filled my nostrils, and I reached up in the dark to touch some of the fruit. We stopped for a moment to grab a handful each. Most of the guavas were ripe and delicious. We munched down a few, and then stuffed our pockets before moving off again.

Like that time during Junior Leader training when I passed through an orange grove, it was an invigorating moment. It completely revitalised us in body and spirit. We were in high spirits after eating the guavas, in spite of our failure and the likelihood that every FAPLA and Cuban soldier in southern Angola was looking for us.

We moved on and just kept going, hour after hour. At mid-morning a shower of rain erupted. We made good use of the downpour, and were thankful that the few tracks we might have left were now obliterated. Only late that afternoon, when the rain had subsided and our clothes started to dry on our bodies, did we stop for a cup of coffee and something warm to eat. Far off to the northeast we could hear aircraft and helicopter movement, but, except for a few MiGs passing high overhead, no aircraft came any closer.

We travelled through most of that night, but were too tired to keep up the pace and slept for a few hours before daybreak. We found good cover on a rocky outcrop, and carefully listened throughout that day for any reaction. We knew the enemy would search further from their base, and would likely apply the tactic – which all three of us had encountered before – of dropping off soldiers to patrol dry river beds or set up OPs in areas where they could dominate the terrain.

On the third morning we reached the pick-up point, having walked more than 60 km in the rough terrain. We used the whole day to watch the LZ area, as we didn’t want our helicopters to run into trouble. Our pick-up arrived just before last light and the three of us jumped into the first helicopter, as we were much lighter than during the infiltration. The pilot told us that Oom Boet Swart was on board the second helicopter and conveyed his greetings. We then settled into the job of watching out for enemy aircraft. I got a fright when I suddenly saw a fighter against the skyline, but the crew reassured us that they were our own Impalas escorting the helicopters.

Once we crossed the border into South West Africa, we veered left and headed for Ruacana, while the second helicopter had to go back to Opuwa to pick up the forward Tac HQ established for the pick-up. We refuelled at Ruacana and then flew back to Ondangwa where a feast awaited us at Fort Rev.

We sat down to our meal as the second helicopter came in, and waited for Oom Boet to make his grand entry. But then someone came rushing in to say there had been an accident – Boet Swart had been run over by a helicopter. We rushed out to the apron and found Oom Boet in a pool of blood on the tarmac. The doors had been opened while the aircraft was still moving and Boet, recognising the familiar lights of Fort Rev in front of him, thought they had come to a standstill. He descended the steps and fell – directly in front of the aircraft’s wheel. Gees Basson, fortunately a very experienced pilot, pulled up immediately when he felt the obstacle, not realising it was Oom Boet. This ensured that Oom Boet was not crushed by the full weight of the helicopter.

Late that night, while standing with the other Small Teams operators around Oom Boet’s bed in the sickbay at Ondangwa, I once again realised what an extraordinary individual he was. He had just undergone emergency surgery and was about to be evacuated to 1 Military Hospital in Pretoria. He was practically on his deathbed. We were called in to say our farewells, and stood with tears in our eyes, when Oom Boet suddenly spoke, in a faint but clear voice.

“Small brains, what are you doing here around my bed?”

Diedies replied that we had come to greet him, and he asked mischievously, “So where are you all going, then?”

During the extensive debriefing process back at Special Forces Headquarters, we spent many hours inventing and analysing ways of engaging enemy aircraft guarded by troops sleeping underneath them. Various devices that could be set up at a distance of 30 or 40 metres from the target were evaluated, but in the end the authorities decided there would not be a third Operation Abduct, as it was evident that the enemy were expecting us to attack their fighters, and the risk of penetrating an enemy airfield was now considered too high.

Operation Abduct might not have been a success, at least not in terms of its strategic aim, but for each of us – the three operators who had prepared for months, spent countless nights rehearsing and finally executed that mission – it was a personal success. In all aspects it was a classic Small Team deployment that tested our skills, endurance and dedication to the limit. In the end it turned out to be the life-changing experience I had expected it to be. I knew that in future I would prepare the charge and stalk that aircraft with the same dedication, any time, every time.