3

Operation Killarney

December 1985 to January 1986

“The first principle of the art of stalking is that warriors choose their battleground. A warrior never goes into battle without knowing what the surroundings are.”

BY THE MID-1980s the civil war in Angola was at its height. The MPLA focused its efforts on Jonas Savimbi’s UNITA in the eastern part of the country, while South Africa supported UNITA with rations, equipment, ammunition and vehicles. Behind the scenes, the Americans directed substantial financial aid to UNITA because they were still concerned about the communist threat, especially in light of Russian and Cuban support for the MPLA.

The supply lines in support of the MPLA offensive against Savimbi relied on the delivery of huge amounts of stores and equipment to the ports of Namibe and Lobito. In the case of Namibe this material would then be transported by train into the interior to Lubango. From Lubango, Russian cargo planes ferried supplies to the forward airfield at Menongue.

Operation Killarney

The Namibe–Lubango railway line carried a substantial part of the logistics for both the Angolan forces and their SWAPO brethren, which of course made it a priority target for the SADF. The Recces had indeed launched a number of operations to render the logistics ineffective, one of which was an attempt to demolish the rail tunnel at Humbia, another to destroy the road over the Serra de Leba pass in October 1979. There were also several unsuccessful attempts to destroy the road bridge at Xangongo.

Diedies had previously convinced the bosses that two-man teams could disrupt rail traffic for substantial periods at low cost and with minimal risk. Over the course of two years two Small Teams – Diedies and Neves, and Tim Callow and Paul “Americo” Dobe – had repeatedly deployed in southwestern Angola, laying mines along the exposed railway line and bringing traffic to a virtual standstill.

During the same period EMLC conducted wide-ranging research on various types of explosive charges and methods of detonation that could effectively derail a train, destroy the engine and cause enough damage to the track so it could not be repaired easily. However, there were certain challenges that had to be considered. The Angolan forces patrolled the line on a daily basis, checking for disturbances on the track. Intelligence confirmed that an empty carriage was also placed in front of the engines to detonate any charge before the engines could set it off. All trains carried armed escorts, while culverts and curves in the line were especially well monitored as they were considered vulnerable or potential targets.

By the end of November 1985, barely a week after our return from the previous deployment, we were back in the ops room at Phalaborwa to be briefed for the next mission. Present were Dave Scales, Neves Matias, Jos? da Costa, CC Victorino (“Vic”), me and some intelligence support guys. Operation Killarney was aimed at causing maximum damage to the railway line. EMLC’s latest invention also had to be tested.

Our ops briefings always started with the counterintelligence brief, followed by an intelligence overview, after which the ops commander would convey the mission. Eric McNelly, taking personal responsibility for Small Team deployments, was again there for the counterintelligence brief. He explained the details of the security risks we would be facing once we were at Ondangwa, since SWAPO ran a comprehensive spy network in Ovamboland and any new activities in and around Fort Rev would be reported.

Then Dave Drew gave us an overview of how SWAPO received its logistics. Supplies went mainly by train from the port of Namibe via a distribution base at Lubango, then to the operational front headquarters, and eventually by truck to the detachments on the ground. He zoomed in on the area between Lubango and Namibe, describing the topography and vegetation of the semidesert terrain, and finally highlighting the railway line, the types of trains that were used and the frequency of the log runs.

Since Diedies would be on a course during our preparations for Killarney I was appointed mission commander, while Oom Boet would be the Tac HQ commander.

“The cover story for the deployment is that you will be going on a Small Team training exercise to Sawong,” Eric McNelly said, “which will actually be the case. You will spend two weeks at Sawong for rehearsals, and then move to Pretoria for the second stage of the rehearsals as well as final planning and briefings.”

Rehearsals at Sawong followed the usual pattern of exercises to condition our minds and bodies for night work. We would use the hours of darkness to practise team drills and rehearse every contingency. Much time was spent on patrol tactics, anti-tracking and emergency procedures. In the early morning, after a full night’s work, we’d do a strenuous PT session, carrying our buddy or running with backpacks. After catching a few hours’ sleep in the morning, we’d brush up on first aid, often administering drips to ourselves. During daylight hours we honed our communications skills, concentrating on sending and receiving Morse code. During the hottest part of the day we worked on recognition of enemy weapon systems.

After two weeks of intensive preparation, we departed for Pretoria. I went in my own car since I wanted to spend time with Zelda before the deployment. Although I had battled with my feelings for her for a long time, our relationship soon grew into much more than a friendship. Whenever I was in Pretoria on business, I stayed with Zelda and her family in the affluent Waterkloof Ridge neighbourhood. We were very fond of each other and had wonderful times together, but soon the secrecy of my job and the uncertainty of our long-term deployments started to affect our relationship.

Hiding the true nature of our forthcoming deployment introduced some complications, since by then Zelda had some grasp of Special Forces and the type of operations we were involved in. Since she had met Diedies and some of my comrades, she was part of the “inner circle” of Small Teams and had a fairly good understanding of our job. As far as our families were concerned, I would be doing one of the regular long-term stints on the border, as was common during that time.

After the weekend with Zelda I moved back to the Karos Hotel in Pretoria, where we stayed at reduced rates when the officers’ messes were full. Our rehearsals now became more focused, as we needed to master the technicalities of railway demolitions. Specialists from EMLC taught us the intricacies of working with a mine, code-named Pick, tailor-made for diesel-electric trains. To ensure that the charge would not detonate when an empty carriage was coupled to the front of a train, Pick was designed to activate only once a diesel-electric locomotive passed over it. The device could be programmed to remain in sleep mode for up to three months, and then to arm itself and wait for the approach of a diesel-electric unit. The device had a little antenna that would pick up the electromagnetic field generated by the electric motor (the diesel engine in a diesel-electric unit is primarily there to generate power for the electric motor that drives the train), thus activating the mechanism. It was also fitted with an anti-lifting device that would react to any disturbance of the mine.

The explosives used for trains, code-named Slurry, consisted of an RDX base washed out of PE4, then mixed with nitro-methane to form liquid explosives. Aluminium powder was added for incendiary effect. The advantage of Slurry, which we carried in thickly sealed plastic bags, was that it could be poured into a hole made in the ballast of the train tracks. It would trickle down into the open spaces and fill all the cavities among the ballast. When exposed to air Slurry would eventually settle and slowly turn into a solid. The complete charge, Pick and Slurry, would be positioned to derail the train and cause maximum damage to the diesel-electric unit.

Various other devices, some extremely advanced for their time, were invented by EMLC and tailor-made for operations. Working on a similar basis as Pick, a device called Shovel was designed for vehicles, while the charge accompanying it was Hydra, a robust explosive that could be formed into all kinds of shapes – even resembling elephant dung strewn on the road surface! Another device I would get to know intimately was the mechanism used for demolishing aircraft, called Tiller, and its specially designed charge, Havoc, consisting of the explosive Torpex based on a solid aluminium plate for incendiary effect.

We visited train shunting yards and various stretches of track to get a grasp of the new challenge. It was important for us to understand the impact explosives had when placed in different positions on the track. I learned that, due to its sheer weight, a train could not be derailed simply by an explosion under the belly of a unit or a coach. The rail itself had to be disrupted, while factors such as the curve of the line, the speed of the train and the height of the tracks above ground level had to be taken into account.

By that time we had invented a new technique to prepare the railway site and plant the device: Diedies and Neves had designed a small tent that could be assembled and positioned over the tracks within a few seconds. With the side flaps stuck together with Velcro, the tent was completely light-tight. The operator inside the tent would use a powerful headlamp, allowing him to work fast and effectively and to make sure that, once the hole between the tracks had been filled in and the site covered up, the camouflaging would pass close scrutiny.

One problem was that the top layer of the track ballast, through exposure to the elements, had a different colour and texture from the underlying stones. The operator therefore had to clear the top layer and keep these stones aside to cover the hole again once the job was done. Previously, operators had used night-vision goggles when replacing the ballast, but the unnatural green image created by the goggles often meant that some discolouration would be visible on the surface. Working with white light reduced the risk of poor camouflage, and it certainly boosted the operator’s confidence when connecting and arming the detonating device.

One Saturday night, while I was staying at Zelda’s parents for the weekend, we had a rehearsal on a disused railway line passing through a deserted stretch of land outside Pretoria. Da Costa, Neves, Vic and I spent the Saturday at Special Forces HQ preparing for the night’s work, and departed for the target area as soon as it was dark. Since it was not meant to be a tactical exercise, two of the EMLC technicians joined us to provide technical support and advise us on the placement of the devices.

We got started straight away, but soon realised that digging into the ballast would not be an easy job. Until late that night we worked on various ways to remove the stones and dig into the strata below, testing different types of tools for the job and practising different ways of inserting the devices. At about 02:00 we packed up, satisfied with the night’s work, and started towards the parked vehicles.

We had to cross a dilapidated old fence line and, since my arms were full of equipment, two of the guys held the rusted strands down to help me get across. Then, unexpectedly, a single strand snapped loose and ripped across my face, one of the wire knots tearing open my upper lip, strangely enough on the inside, as I must have had my mouth open at that moment. In an instant blood was spurting all over the place. The operators rushed me to 1 Military Hospital, where the wound was stitched up. A heavy dose of painkillers and antibiotics rounded off the treatment.

I wasn’t a pretty sight when I quietly slipped into Zelda’s folks’ home in the early hours of the morning, but everyone was asleep and I got to bed without anyone noticing. But eventually I had to get up and show my badly swollen face. I had barely slept due to the pain and discomfort. I looked decidedly rotten as I walked into the kitchen, where Zelda, her folks and her brother were having their Sunday-morning breakfast.

Zelda’s mom immediately assumed that I had been involved in a bar brawl – “so typical of the Recces”. There was no way of explaining this one away, having disappeared from their home on a Saturday and returned at some ungodly hour with a face apparently smashed to a pulp. To this day they believe I told them a tall tale. It took much explaining just to convince Zelda, but eventually she accepted Vic’s version, as she adored and trusted him. She gave me a hard time for causing damage to my pretty little face.

We now moved to a phase of detailed planning for the deployment, spending many hours on the execution of the deployment, and on routes towards the target areas and the actual points on the line we wanted to attack. As usual, we meticulously worked out and rehearsed emergency procedures for every possible contingency. At the Joint Aerial Reconnaissance and Intelligence Centre (JARIC) at Waterkloof Air Force Base, bent over maps and aerial photos of southwestern Angola, we worked out the details of every leg, emergency RVs and escape routes.

JARIC had state-of-the-art facilities, and for the first time I had the amazing experience of “riding” the stereoscopes. Enlarged stereo pairs of photos covering the target area were laid out under a massive stereoscope. The operator would get into a seat and steer the scope across the photo sets, which would allow him to fly virtually over a landscape that would “jump” out at him in 3D. The experience was so realistic that I became nauseous after a few minutes’ “flying” in the machine.

Then the day arrived on which I, as the mission commander, had to do the in-house ops briefing for the deployment. While I was mentally and physically exceptionally well prepared for the mission, presenting our plan seemed like an insurmountable hurdle. I couldn’t imagine selling my story convincingly to General Joep Joubert, then GOC Special Forces, and all his staff officers. In those days the mission commander would normally do the “in-house” ops briefing to the GOC, followed by a briefing to the Chief of the Defence Force the next day, given that the mission had been approved at Special Forces level.

In attendance at the in-house briefing would be all the staff officers involved with the operation as well as representatives from other departments and arms of service. The Air Force would be represented by the air liaison officer (ALO) dedicated to the deployment, while the medics would be represented by the OC 7 Medical Battalion. The plan would only be approved if all these elements were able to provide support.

As it turned out, my first briefing as mission commander to the GOC Special Forces proved to be more challenging than crawling into enemy-infested targets in hostile countries.

Commandant (the rank was later changed to lieutenant colonel) Ormonde Power, the Ops officer dedicated from Special Forces HQ to the operation, started with the introductions and presented the mission, and then Dave Drew covered the intelligence picture. By the time he introduced me I was almost paralysed by nerves. From the start my transparencies got mixed up, which caused me to start fumbling around with my notes, and I lost my thread. Eventually General Joubert stopped me.

“Stadler,” he said, “what’s this circus? You want to do this operation or not?”

I was nearly in a state of panic. All our hard work, the long hours of preparation and nights of rehearsals were at stake.

“Yes, General, we want to do it, and we are very well prepared,” I managed to blurt out.

“Forget your bloody notes; tell me the story,” he exclaimed.

Then, probably to help me save some face, he started asking me questions about the deployment.

“I want to hear your mission again.”

I ran through it without even glancing at the pinned-up mission statement.

“Now, tell me what it is you really want to do.”

General Joubert was addressing me like the mildly impatient father of a son who had arrived home from school with poor marks.

“Okay, now take me through your execution, step by step…”

This I could do well, since the map of our deployment was ingrained in my mind, and I had every single detail of the mission at the tips of my fingers. I took the general through every phase, explaining the details of the infiltration, execution and exfiltration on the map in front of them. Knowing that the Air Force would take issue with it, I explained the emergency procedures in the finest detail – our escape and evasion (E&E) route, emergency RVs, when and where we would like the telstar (comms relay aircraft) to fly if communications were lost, identification procedures and emergency extraction requirements.

At the end of the briefing General Joubert half-turned in his chair and, in typical fashion, stared at the staff, and then asked: “Any issues, anyone? Can you support the trooper?” I didn’t even blink at the sudden demotion. I knew I had stuffed up badly. But, aside from a few technical clarifications, there were no further issues and the plan was approved.

That, however, was not the end of my woes. Sitting quietly next to General Joubert throughout the presentation was the fierce and, I must add, much-feared Brigadier Chris “Swarthand” (Black Hand) Serfontein, then the second-in-command of Special Forces. As I packed up my aids, Swarthand walked up to me, gripped me firmly by the wrist and ushered me out of the ops room to his office.

“Where do you come from? Have you never learned to do presentations? Haven’t you done Formative?” he asked, referring to the leadership and management course all young Permanent Force officers had to complete. Now I expected the worst.

I started mumbling, but the brigadier forced me to sit down at the conference table in his office, and then walked around and sat opposite me.

“Do you realise that, now that the operation has been approved, you are presenting to the Chief tomorrow?”

Swarthand was spitting fire, his eyes boring into mine.

“Ja, Brigadier.”

“Are you going to stuff up as badly tomorrow as you did today?”

“No, Brigadier.”

“Now listen carefully…” he said pointedly. “Go and fetch your aids and bring it here. Let me show you a few tricks.”

To my surprise, Swarthand Serfontein then took the rest of that day to show me how to do an ops briefing, explaining the nuances of effective communication, style and language. He forced me to repeat every single part of the briefing over and over again, there in the privacy of his office, and patiently corrected me whenever he thought I could do better.

Late that night, at the Karos Hotel, I got a phone call from Dave Drew. “Koos, I hate to tell you this, but the general does not want you to present tomorrow,” he said. “I am to do the Int and the Ops briefing – on your behalf.”

I was furious, but what could I say? Dave was obviously just conveying the message from the general. I left it at that and went to bed, thinking hard about how I would handle the situation.

The next morning I phoned Serfontein. “Brigadier,” I said, “this is my operation. If anyone is to present it to the Chief, it’s me…”

And that was it. Swarthand Serfontein didn’t hesitate. “You go ahead; I’ll mention it to the boss. Just do your best,” he said and put the phone down. Just like that, no questions asked.

Dave Drew picked me up at the hotel and we drove together to Defence HQ. He thought it wise not to argue the point when I told him that I would be presenting the ops plan. We arrived early and set up maps and other aids in the conference room of the Chief of the Defence Force.

The General Staff took their places, and I desperately looked around for a rank that I could more or less associate with, but the lowest was a brigadier. The Chief’s aide-de-camp, a captain, was not even allowed near the briefing room. General Jannie Geldenhuys, then Chief of the Defence Force, entered and sat down at the top end of the table.

My moment of truth had arrived. As usual, Dave did a magnificent job of sketching the strategic picture and highlighting the enemy activity in our area of operations. Then it was my turn.

But this time I was prepared. I let the mission unfold on the map like some mysterious adventure, exactly as Brigadier Serfontein had suggested, then talked them through the resources required and ended off with a summary of the emergency procedures. Once I had finished, there was a brief discussion about the political repercussions if the operation failed, if a helicopter went down or if one of us got caught.

At the end General Geldenhuys sat back in his chair and addressed me across the room: “Lieutenant, tell me, what is your gut feel, is this going to work?”

By now I had worked up an overdose of courage, since, from the reactions round the table, I could sense that the operation was on. “Yes, General, we are very well prepared and I have no doubt that we’ll pull it off,” I said without hesitation.

The General seemed satisfied. The deployment was approved and the meeting adjourned, leaving Dave and me with a great sense of accomplishment. Back at Special Forces HQ Brigadier Serfontein called us in and congratulated us. He had been informed by the Chief’s office that we had presented an excellent briefing and that the boss was impressed by our performance – apparently one of the best he had ever heard!

I felt like an upstanding citizen again, and I am forever indebted to Swarthand Serfontein for lifting me up from the gutters of humiliation that day and for restoring my pride!

A C-130 brought Oom Boet Swart, Dave Scales and all the Tac HQ equipment from Phalaborwa and picked us up at Swartkop Air Force Base for the flight to Ondangwa, where we had a week for final preparations. The Tac HQ was set up in one part of the old jail in Fort Rev, and Dave wasted no time in setting up comms equipment and testing frequencies. The operators made final preparations to their kit. The Pick and Slurry were prepared and distributed among the teams. Each operator would pack a minimum of 30 litres of water, while an additional 30 litres for each would be packed to cache at the drop-off LZ.

As usual, a lot of time was spent on emergency procedures. We talked endlessly through the contingencies and role-played various scenarios with the Tac HQ. The final kit inspection was done in minute detail: all equipment was unpacked and rechecked for functionality and non-traceability. Batteries were checked and recharged where required; radios and electronic equipment were once again checked and tested to ensure they were both serviceable and “sterile” (the term used for non-traceable).

On the afternoon of the deployment the teams were trooped with two Puma helicopters to Okongwati in Kaokoland. Oom Sarel Visser, 5 Recce chaplain, and Oom Boet accompanied us while Dave manned the radios back at Fort Rev. At Okongwati, in a secluded spot under the trees away from the helicopters, we changed into our ops gear – mostly olive green with some pieces of FAPLA uniform – while the crews refuelled the helicopters. As we waited for last light, Oom Sarel put on his United Church of the Conqueror cassock, read from the Bible and gave us a short message of encouragement before giving communion to the teams. This was a custom unique to Small Teams that not only lifted our spirits but also strengthened the bond between us.

We took off before last light and crossed the Cunene River into Angola while visibility was still good. Vic and I were in the first Puma, with Neves and Da Costa following in the second. While there was still enough light, we kept the doors open and helped the pilots observe the skies for enemy aircraft, but all seemed quiet. When it grew too dark to see, we closed the doors and the pilots switched to night-vision goggles.

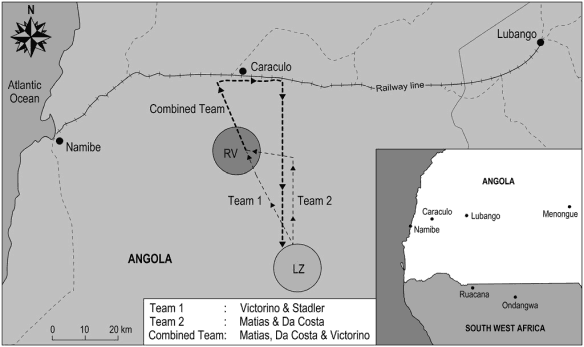

The drop-off LZ was about 40 km from the railway line in the rugged desert terrain south of Caraculo, a little settlement on the plain between Namibe and the Serra de Leba pass. We had picked one LZ for both teams, since it would serve as both the main emergency RV and a cache for the reserves. From there the teams would split up to approach their different target areas, the idea being to cover a wider stretch of the line. Each team would plant three charges five kilometres apart. All charges would activate within 30 minutes of priming, but had been set with different time delays so that they would come “alive” at different times over the next six weeks, ready to be detonated by the first diesel-electric unit that passed over them.

The LZ, in a grassy valley between sloping ridges, had been carefully picked. The moon was approaching first quarter and the pilots found the spot easily enough. The landing went off without any glitches. While the second Puma circled the area, Vic and I quickly offloaded the backpacks, water bags and crates of reserves for the cache. Then we kept a lookout while the procedure was repeated with the second helicopter.

Once the helicopters had departed, we moved into a defensive position around the LZ and waited, listening carefully for any sounds that might indicate the presence of enemy or local population. To me, this was always the worst part of any deployment. As the noise of the helicopters faded away to the south and the silence of the night became almost tangible after the rush, I was overwhelmed by a feeling of loneliness. But I kept these thoughts to myself, as there was a lot to do before daylight.

After an hour’s listening, we converged on the pile of reserve equipment and started caching the crates and water bags. It was slow, painstaking work, as we had to dig a separate hole for each item, bury it and camouflage it. Then the exact position was carefully logged by means of a sketch in relation to objects and features in the area. All the time one of us would be positioned on higher ground away from the activity to listen for any sound of approaching enemy.

By first light we had finished. The two teams had moved into separate positions on high ground overlooking the LZ area. Well camouflaged and with good vision on approach routes, we waited out the day, calling in on the VHF every hour to check if the other team was okay. All appeared quiet, and by late afternoon we decided to move out that night. Before last light Neves approached the cache to ensure that it was undisturbed and still properly camouflaged.

Vic and I would take the area west of Caraculo, while Neves and Da Costa would go 20 km further east. I had not expected the going to be as taxing as I experienced it that first night. My backpack weighed in excess of 85 kg, which was more than my own body weight, and it took great effort to get it on my back and to stand up. For a main weapon, I carried the Hungarian AMD-65, a modified version of the Russian AKM assault rifle, while Vic had a silenced weapon, the MP5 SD.[13] It had become standard practice for teams to have a normal (unsilenced) firearm and a silenced weapon as main armament. Each operator would carry a pistol of his own choice as a secondary weapon. I had also taken it upon myself to do the navigation, which I routinely did during subsequent operations, as it was a skill I liked to practise and which I believed I had perfected to a fine art. But on this first deployment it was a challenge to navigate the rugged mountainous terrain while carefully applying patrol tactics and anti-tracking techniques.

By midnight, having covered only two kilometres, we were already bone tired and decided to move into a hide and rest. At first light I went up the mountainside and kept a lookout for the day while Vic stayed with the kit. From my vantage point I could see our route stretching north through the barren countryside. It was very uneven terrain, and I realised that we needed to pick up the pace and at the same time preserve our precious water.

We moved out by late afternoon, utilising the last light of the day to make up for lost time. We had agreed to cover ten kilometres that night, although I knew it was a tall order. But in the valleys among the mountain ridges the going was comparatively easier and we finally settled into a steady pace.

But I was not destined to see my first operation through. In the early hours of the morning, having covered most of our intended stretch for that night, I stepped on a loose rock and badly sprained my ankle – the same one I had injured in the night contact with 53 Commando at Nkongo the year before. I tumbled down the slope with my kit. The moment I managed to disengage myself from the heavy backpack, I realised I was out of the game. Within minutes my ankle was swollen, and no matter how we strapped it up, it wouldn’t fit into my boot. There was no way it would sustain the weight of the kit.

My predicament left us with few options. A helicopter evacuation so close to Caraculo would mean certain compromise, but Vic could not carry all the equipment and finish the job alone. The only solution was for Vic to join the other team while I waited in the area. So it was decided that the other team would move in to our position. We would then rearrange the equipment so that the newly formed three-man team – Neves, Da Costa and Vic – could carry five charges. I would remain in the area until their return.

Fortunately Neves and Da Costa, having made about the same progress as we had, were no further than four kilometres to our east. Through the Tac HQ we arranged for an RV at a prominent feature close to us, and late that afternoon Vic went to meet them and led them to our hide.

I kept enough food and water to last me another seven days and gave the rest to Vic, while I took the HF radio. The team also took one Pick and enough Slurry for one charge from me. Between the three of them they would still be able to place five charges.

At last light they disappeared into the night. After the noise and movement of the repacking, I decided to move out and find a new hide where I would feel more secure. I cut my boot open and forced my strapped foot inside, then wrapped it all up again with dems tape (an exceptionally strong adhesive tape used in the preparation of demolitions). Moving around was slow and painful, but I managed to cover about a kilometre and settled in a good hide halfway up the slope of a mountain.

What followed was an extraordinary experience, even though I was no longer taking part in my own carefully planned operation. I was used to being alone and doing my own thing; in fact, I took pride in being able to live with my own good company for long periods. In the past I had often gone on solo hiking and camping trips, which I enjoyed immensely and always used as opportunities to cleanse body and soul. But this was a new experience, as I now had to deal not only with the loneliness but also with the threat of discovery by the local population or FAPLA. Although the rugged mountainous terrain offered good cover and excellent escape routes, there was almost no vegetation, and I had to take great care not to expose myself during daytime. As I knew that I would be hampered by my injured ankle if located by the enemy, I carefully applied proper tactics. By that time anti-tracking formed part of my everyday routine, but I still made sure I left no sign of my presence.

We had agreed to stick to the same radio scheds so I could receive the team’s messages and monitor their progress. Dave Scales was as prompt and efficient as ever. He got both teams in the hopping mode[14] simultaneously and let Da Costa transmit the team’s message first. Then he closed them down and had me transmit my message. I was surprised to learn how much distance the team had covered. Two more nights and they would be at the target.

Over the next seven days Dave Scales became my closest companion. We had two scheds a day, but the afternoon call was aimed mainly at boosting morale and guiding me through the long hours of hiding. Dave would check if I was on the air and then start an extensive broadcasting regime. He shared snippets of news from home, read newspaper cuttings he thought I might find interesting, and told jokes. This was essentially a one-sided conversation, as I could not afford to transmit, both to save battery power and to avoid detection by enemy electronic measures. However, Dave, who broadcasted from the base station at Ondangwa, could chat away – an opportunity he wouldn’t have passed up.

Every day Billy Joel’s “Piano Man” would be carried to me on the airwaves, since the song is all about loneliness. To this day, whenever I meet up with Dave or call him on the phone, our opening line is always “And he’s talkin’ to Davy, who’s still in the Navy/And probably will be for life”, from that touching song.

The team made good progress, and, two nights later, after observing the railway line for a full day, they started placing their charges. They planted the first one west of Caraculo, and then started working east towards the Serra de Leba mountains. By the time the second mine had been planted, they were fifteen kilometres east of the position of the first charge, the area where Vic and I would have operated. Since they were still heading east, it wouldn’t make sense for them to return to my position once the job was done. They were running low on water and had a long distance to reach the RV. I therefore decided to start moving back towards the LZ area so the team could head straight there.

I moved only at night and took exceptional care with my injured foot. Before first light I would find a hide as high up the mountainside as possible and spend the day observing the trail I had covered during the night. By this time I was also low on water, but kept a strict routine and refrained from drinking during the day.

I reached the cache area on the seventh night after splitting from the team, a few days before they would arrive. I was now out of water, but forced myself to observe the area for another day before moving in. Just before last light I approached the cache, having left my kit in a hide up the mountain. The area was undisturbed and all the caches untouched. Very relieved, I removed a water bag and took it back to my hide, from where I kept a lookout while I waited for the team.

When they arrived a few nights later, I had already taken some stock from the cache, as they were completely out of water and running low on food. They reported that they had used all the Slurry to beef up three charges planted over a distance of 20 km.

We were picked up by the two Pumas late the following afternoon. After refuelling at Opuwa, we headed straight back to Fort Rev, where oom Boet Swart and Dave Scales had prepared a five-course meal as a welcoming feast for us.

Over the next few months we received three reports from Intelligence at Special Forces HQ of diesel-electric units that had detonated charges on the line between Namibe and Lubango. Rail traffic came to a halt as the train drivers started to refuse to travel on that stretch. In spite of FAPLA’s efforts to locate and destroy the mines, the charges kept exploding one after the other, always targeting the diesel-electric unit itself.